Coverage of the issue of prisoners of war in the media: problems and the search for solutions | DMF 2024

Coverage of the issue of prisoners of war in the media: problems and the search for solutions | DMF 2024 At the discussion panels of the Donbas Media Forum conference, the invited speakers shared their thoughts on how communication with the world should be organized, what Ukrainian and international media should do, and how the official authorities in Ukraine should organize their communication.

Currently, the families of prisoners of war and the organizations they unite with do not know what conditions their relatives are in. In particular, the relatives of those who survived the mass execution in Olenivka do not know about the fate of their relatives in captivity. While in 2022, Russian propagandists tried to show footage of victims and survivors, there is little information now.

According to Oleksandra Mazur, head of the Olenivka Community NGO, her organization is open to media interviews, and the families of those killed and those who returned from captivity are willing to give comments to Ukrainian media. Western media, on the other hand, are harder to interest.

“We cannot break through this ice. We are turning to foreign media, but it has almost no effect. We very rarely have publications abroad. As we understand it, as Ukrainian journalists tell us, this is because they have no interest. It’s just not relevant to them,” said Mazur and urged journalists to share the contacts of NGOs of POWs’ families with foreign media.

Olena Barsukova, a journalist with the Ukrainian Pravda Life publication, also sees a problem with insufficient ethical communication on the part of journalists. According to Borsukova, every person — prisoners of war who returned home and their families — had a negative experience with journalists.

“For me, it’s not okay, and the problem for me is that our media loves to squeeze out emotions, that is, to make the family cry… It is possible to find a way to talk about painful emotions and living with separation from a loved one who is in captivity with the help of text, not by squeezing out crying or desperate phrases from the families of prisoners. The person is left with this pain afterwards, and you just go away and forget everything. But a person lives through the same thing in every interview,” Barsukova said.

The journalist believes that another problem is excessive attention to the military when they have just returned from captivity: excessive concentration on tears, weight loss, hugs with relatives, and the violence they experienced. It is unacceptable to assume what a person has experienced in captivity. Some prisoners, according to the journalist, complained that their conversations near the bus were published without permission.

“There is a way to do this ethically. You can establish simple friendships, go to rallies, meet families, get to know the guys and girls who are returning. This will bring a much more emotional response than a quick attempt to poke a person and leave,” the journalist says.

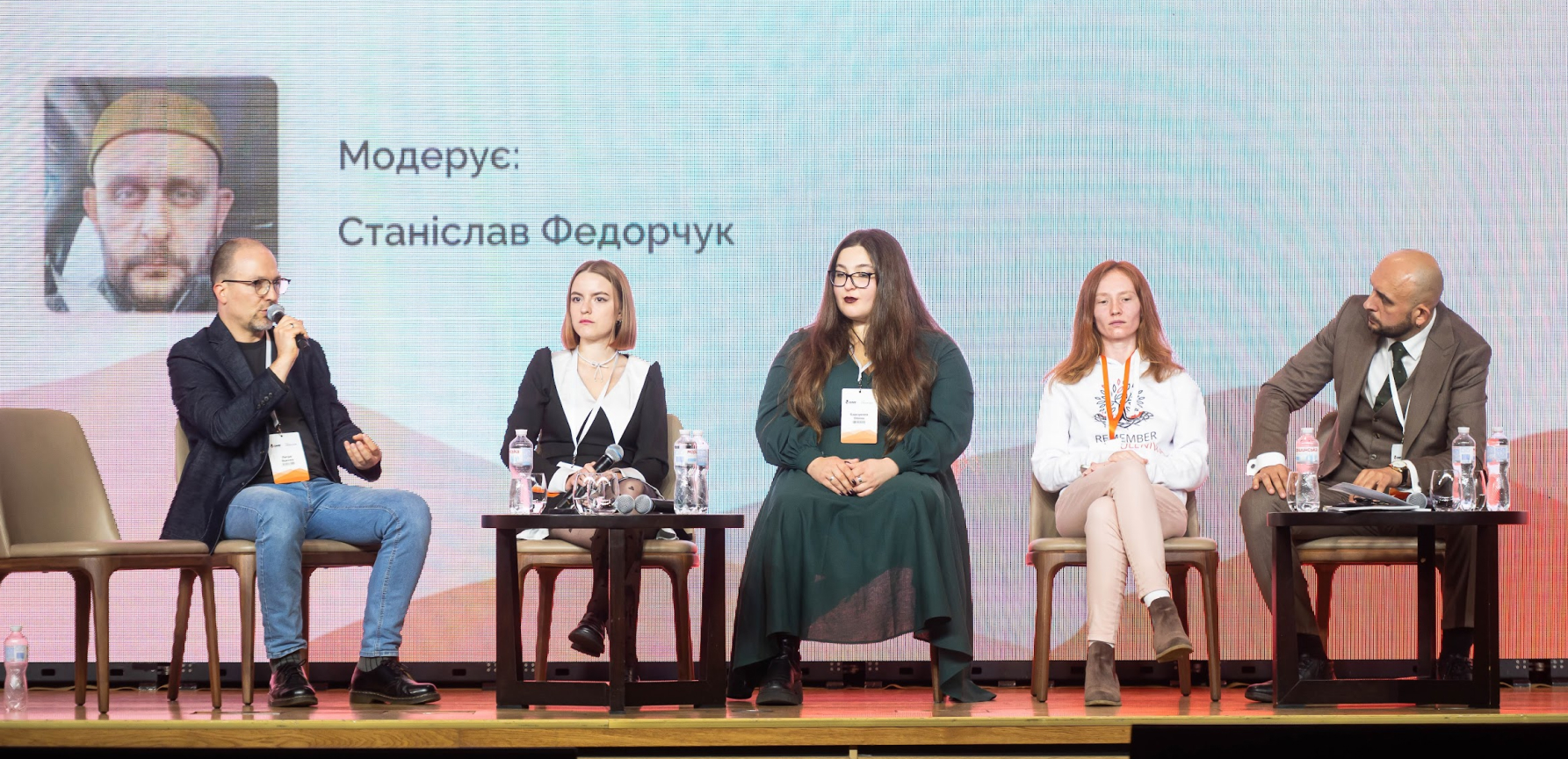

The moderator of the discussion, Stanislav Fedorchuk, Chairman of the Board of the Ukrainian People’s Council of Donetsk and Luhansk, noted that it is very important to talk about our prisoners of war as people who are part of the Ukrainian Defense Forces, including during their time in captivity.

Daria Hryhorenko, a journalist at Suspilne, has had a number of publications related to the ethics of communicating with the families of prisoners of war. She believes that a journalist should not chase a sensation, because first and foremost, they are a human being, not an object to be presented as a sensation.

“First of all, I tell my interviewees that I don’t want to tell a sensation, I just want them to share their own experience and for anyone who has faced the same situation, experienced what they have experienced, to realize that they are not alone,” explains Daria Hryhorenko.

In her opinion, it is important to let the family of the prisoner understand that their child is important and that they are remembered.

Petro Yatsenko, representative of the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, emphasized that the main principle that journalists should use when working with prisoners of war is “do no harm.” More than 95% of military and civilians who returned from captivity were tortured.

“Every time after an exchange, we introduce a two-week quarantine for the media to communicate with these people. We try to observe it because people need to come to their senses, they need to understand their condition. They work with doctors, they work with psychologists. And after these two weeks, you can’t communicate with everyone. You can only communicate with those who have permission from psychologists, who have something to say and want to do so. Sometimes these states are unstable. Sometimes these people agree to talk to the media, but at the last minute they refuse,” says Yatsenko.

He advises that when communicating with prisoners of war, one should focus on the positive aspects, on what supported the person in captivity, what helped them survive. Now people who have been in captivity for more than 2 years are returning from captivity, and they need more time to start talking freely about the terrible things that happened to them. It is advisable to have a family member or a psychologist with experience working with military and civilians who have been captured with this person during the interview. In no case should you ask anything or ask provocative questions or anything like that.

Nevertheless, Mazur believes that Ukrainian media closely follow the actions in support of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Partnerships have been established with many, and journalists are willing to attend events.

“They (the actions in support of prisoners of war in Ukraine – ed.) have a high level of contact with the media, and we can see it. Photos from the actions in Ukraine are constantly published, especially in Kyiv. Other cities publish regional media. Everything is fine, it’s been established,” she said.

Instead, diaspora organizations have problems. They do not receive funding, do not have special photographers on staff who would publish photos immediately after the event. This becomes a problem for the Ukrainian media, which does not want to talk about a rally that took place a few days ago.

In turn, the Western media publish news about Ukrainian prisoners of war only if there is an interesting news story. Reminder actions are no longer in the focus of their attention. Olena Barsukova believes that we need to constantly create newsworthy events.

“We need to understand their specifics. What is our daily pain for us is just another problem for them, somewhere far away. They write about the prisoners, mostly only when there is a newsworthy occasion, so it is good to create newsworthy occasions. For example, when families go to see the Pope or give speeches in Geneva. This is already a newsworthy event. They write more often about the statements of the President’s Office, the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Coordination Headquarters, or the GUR. Therefore, these statements are very important. If there is an exchange – especially if there is a large exchange – they also write about it. It’s almost impossible to get them to publish a publication with just an announcement of the exchange or photos from the exchange,” the journalist says.

At the level of the European Union’s political environment, it is recognized that neither the ICRC, nor the UN, nor the OSCE can influence the fate of our prisoners of war and civilian hostages. Stanislav Fedorchuk believes that the media can persuade Western political elites to take a more active stance in finding ways to enhance the exchange of both civilian hostages and prisoners of war. Instead, some foreign observers accuse the Ukrainian media of being too emotional when it comes to captivity.

Instead, Daria Hryhorenko told us which stories are most popular. The journalist believes that readers are fascinated by details, life-affirming motives, and human attitudes toward prisoners of war and those waiting to be released from captivity. Memories of childhood, hobbies, hobbies, hobbies that inspired the person — all this creates a positive image of the prisoner and his family, gives hope, and shapes human attitude. She advises against chasing sensations and squeezing out tears.

“I am sure it will be interesting. Talk about what a person is passionate about. And not to describe the types of torture that the Russians used against her, but to tell about how the person lived, and when she returns from captivity, she will be able to adapt so that she can return to what she was doing,” says Daria.

According to her, a sincere emotional contact between two people united by a common theme is crucial. “Commercial” contact between a journalist and a relative of a prisoner will not work.

“Sincerity builds trust. I put myself in the shoes of a mother whose son was captured. I would not sit next to a stranger who called me yesterday and said: “Can you please tell me a story?” I wouldn’t sit down and tell it, because it’s important for me to see the person, to see their feedback, to see their eyes, to see what they want to hear, so this is also very important”.